Michigan Law Enforcement Faces Challenges with ‘Red Flag’ Gun Laws

Michigan’s impending “red flag” law, set to take effect next spring, is causing concerns for law enforcement agencies across the state. This law aims to address individuals with a high risk of violence by allowing courts to issue extreme risk protective orders that prohibit them from possessing or purchasing firearms. Such orders can be requested by law enforcement officers, family and household members, including those with a current or previous dating relationship, and health care providers. However, as the implementation date approaches, some police chiefs and sheriffs are raising questions about how their agencies will handle these changes.

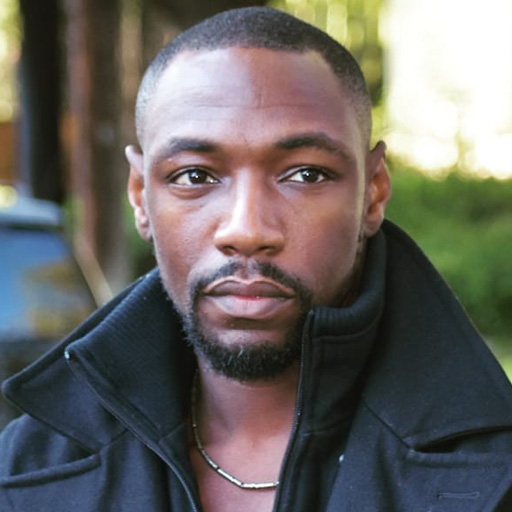

Robert Stevenson, the executive director of the Michigan Association of Chiefs of Police, expressed support for the law, emphasizing the need to restrict firearms access for individuals who are not mentally stable. Still, he raised concerns about the safety of officers tasked with confiscating firearms from potentially dangerous individuals. He questioned how officers would handle situations where individuals resist, attempt to harm the officers, or remain suicidal even when their guns are being seized.

Stevenson’s worries extended to the public perception of these events, fearing that situations where officers have to use force or, worst-case scenarios, take a life, could lead to negative optics. He stated, “We’re trying to save somebody in the family. We went to the police to save them, and they killed them.”

Another police chief, Roger Squiers, acknowledged similar safety concerns but pointed out that working in a small town offered a different dynamic in community policing, where officers are seen as community leaders. Squiers believed that in such a setting, officers could establish better rapport with individuals facing red flag orders and explain that their actions are not intended to be punitive but rather for safety.

However, Squiers also mentioned the challenge of having limited time to research legal and enforcement plans, given that smaller departments often have fewer resources. He expected that law enforcement agencies would provide training when the law takes effect.

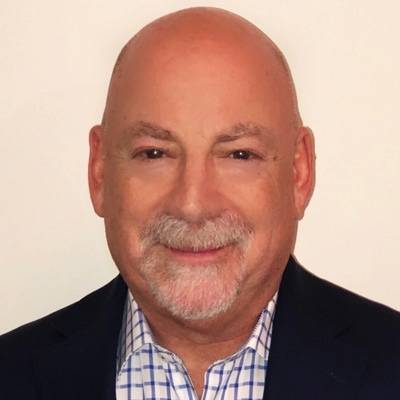

Matt Saxton, the executive director of the Michigan Sheriffs’ Association, raised concerns about not being involved in discussions about how to enforce the new law. He repeatedly requested to be part of the enforcement planning process but was left uninformed about what strategies to develop. He noted that the Michigan statute differed from those of other states, making comparisons difficult. Moreover, there was no statewide standardized enforcement strategy, leaving it to local municipalities to determine their approaches.

Saxton pointed out that, while he doesn’t consider extreme risk protection laws the best solution, he hopes they will help protect the public and law enforcement officers. He also anticipates that law enforcement agencies may collaborate with neighboring departments for support during the firearm retrieval process.

In conclusion, Michigan’s forthcoming “red flag” law has raised concerns among law enforcement agencies, particularly regarding the safety of officers involved in firearm confiscations. While some police chiefs believe community policing dynamics could help, there are concerns about limited resources and insufficient time for planning. The lack of input from state agencies and the absence of a uniform enforcement strategy have added complexity to the situation.