Interior Department’s Shift Towards Indigenous Knowledge Sparks Debate

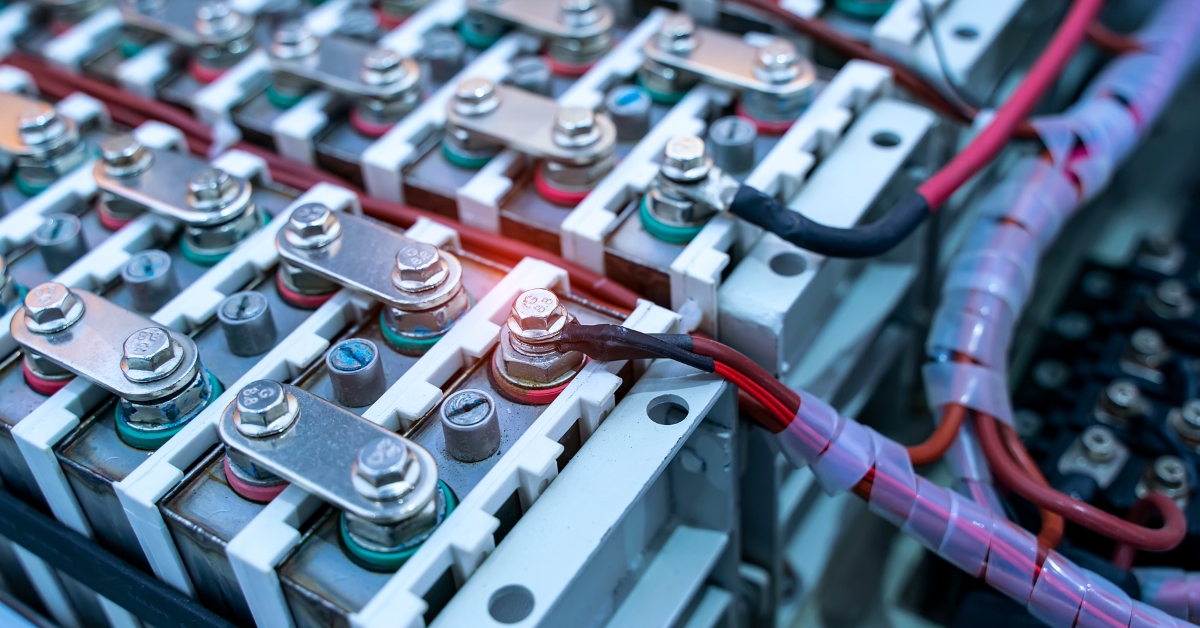

Two years ago, the U.S. Interior Department celebrated its 172nd anniversary by recommitting itself to making decisions based on science. They emphasized following the best scientific practices and adhering to the Data Quality Act of 2000, which set standards for scientific information’s quality, integrity, and reproducibility when disseminated by federal agencies. This approach aimed to put scientists in control, ensuring that science remained at the core of the Interior Department’s mission.

Fast forward two years, and the Interior Department is now advocating for the consideration of knowledge from “spirits.” This shift towards “indigenous knowledge” began with a 46-page memo from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. This memo instructed numerous federal agencies to adopt “indigenous knowledge” for their research, policies, and decision-making processes. While it’s crucial to acknowledge and respect the traditions and knowledge of indigenous communities, the question arises: should this knowledge replace the Interior Department’s commitment to science-based decisions?

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American cabinet secretary, argues that indigenous knowledge about the natural world will be valuable, particularly in the face of climate change. However, the specific language in the memo is perplexing, emphasizing the importance of considering and including indigenous knowledge while respecting the sovereignty and self-determination of tribal nations. This emphasis on knowledge from spirits raises questions about how it can replace science in government decisions.

It’s essential to clarify that respecting the sovereignty and self-determination of tribal nations is unquestionable. However, the shift towards basing government decisions on their knowledge may lead to unintended consequences. Critics worry that this approach could blur the line between admiration for indigenous traditions and reliance on unscientific methods.

Some have written about the history of indigenous communities, questioning the practicality of adopting their knowledge in contemporary decision-making processes. While Native Americans have a rich history and tradition, including their deep connection to the land, they had not designated wilderness areas or acknowledged concepts like endangered species, critical habitats, parks, monuments, or conservation areas. These are things that the Interior Department is responsible for managing, and they must base their decisions on science.

Economist and political philosopher F.A. Hayek raised concerns about America’s growing obsession with Native American traditions. He emphasized that the idealized image of indigenous communities as “happy primitives” who would willingly forgo development for rural poverty was a fantasy. He pointed out that these communities often lived under primitive, tribalist conditions with shorter life expectancies and lacked many benefits of civilization. Today, such viewpoints are met with criticism, but they underscore the importance of not idealizing indigenous knowledge without scientific merit.

While the Interior Department’s shift towards indigenous knowledge may be motivated by a desire to respect traditions and recognize their value, it raises questions about the role of science in decision-making. Ultimately, government decisions must continue to be based on sound scientific principles.

In conclusion, the Interior Department’s recent emphasis on “indigenous knowledge” as part of decision-making processes has sparked debate. While indigenous input should be sought, critics are concerned that this shift could lead to unscientific decision-making. Striking a reasonable balance between honoring traditions and relying on science remains a challenge that must be addressed.